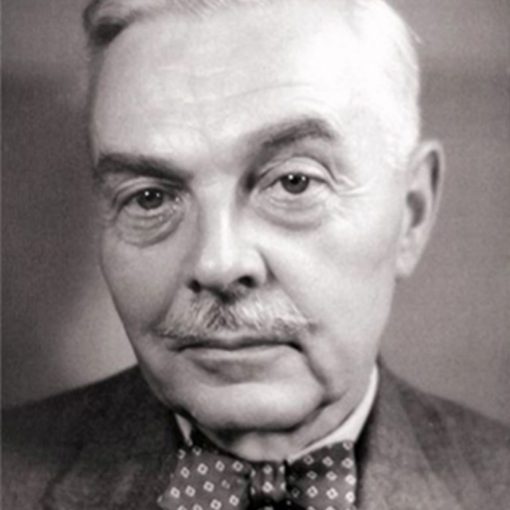

The fraternal and spiritual life of Prof. Dr. Vladimír Wagner narrated by his son Michal Wagner

My father Vladimír Wagner was born in 1911 in Brno in the family of a civil servant. During his youth and early adulthood, at the times of the First Czechoslovak Republic, the family economically thrived.

At high school, my father is an ardent Christian. However, he is gradually losing his faith in the credibility of the Bible. His admiration for Jesus as a historical figure remains unchanged, yet he believes that from existing sources, it is impossible to learn about Jesus enough in order to create our religious life based on this knowledge.

Instead, he moves his admiration towards scientific knowledge and decides to follow the scientific career preceded by medicine studies. Between the wars, science was perceived more as a promising field than it is now in the 21st century. Its proven potential to discover natural laws gave in educated circles hope that new scientific discoveries could speed up the transition towards a more just and spiritually free society. That is why my father then hopes in rational and scientific development based on the idea of a more egalitarian society that leads towards deeper social justice. The beginning of the Nazi occupation catches him as a newly married doctor, who is just starting his scientific career. This career is well described in his memoirs „Symptomy bezmoci: vzpomínky“1 (The Symptoms of Powerlessness: Memories) published by Galén publisher. He describes there mainly the medical and scientific environment. In these memoirs, written during the totalitarian era, he keeps silent about his Masonic contacts.

He admires the contribution of the then-growing intellectual authority of science to society as a whole. However, this does not lead him to the unconditional acceptance of scientific materialism as a worldview. His home library bears witness to his continuing effort to gain as many spiritual values as possible from various sources: history and popularisation of science, intellectual European novels, philosophical works, and texts about practically all world religions.

During WWII, my father is in the resistance. Initially, he collects and shares information for independent Yugoslavia and later for the exile government of Edvard Beneš. Thanks to the courage of his co-workers, Dr. Babok and Dr. Procházka and Yugoslavian Gjurič, who did not betray him even after being arrested and later sentenced to death for their part in the resistance, my father miraculously survives the fall of this group. With Dr. Raška and Dr. Málek, he establishes a connection with the Protectorate prime minister Eliáš. After Eliáš’s execution and termination of this connection, he contacts an illegal resistance cell of the Communist Party, which makes him active in the Communist resistance till the end of the war. After the end of WWII, he quits the Communist Party before the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d’état as he finds out that the Party is spiritually corrupted and dishonest. For his activity in the resistance, he is proposed for a distinction, but the Communists do not forgive him for his exit and critique of the Party. After the 1948 coup d’état, the process to bestow honors on him is stopped. He does not receive it until after the Velvet Revolution.

Nevertheless, he does not lose his faith in the significance of scientific knowledge. He is aware of the debacle of eugenics because of its monstrous misuse by Nazism. Claims of Marxism to be a scientific discipline were also heavily profaned, mainly due to the promotion of fake pseudo-discoveries of Lysenko and his followers. This made my father suffer, with other honest scientists, such as Sekla. My father rightly understood that these and many other issues represent a moral failure of society, not of scientific research. However, after WWII, his optimism towards the influence of scientific progress on society surely partly faded away.

After losing his belief in ideas and praxis of Communism, my father becomes a Freemason, under the influence of Syllaba, Charvát and other doctors. He was impressed by a saying (known since at least the foundation of the Národ Lodge) that a new member will find 9 out of 10 Brethren among Masons being honest and intelligent men, whereas, in society as a whole, the ratio is reversed. Before and after his Initiation to the Order, my father is spiritually a man seeking deeper spiritual truth. He learns about books of five main religions. Analects of Confucius had the biggest impact on him as well as on me. He also knows the Quran, Buddhist and Hindu texts.

The 1948 Czechoslovak coup d’état as well as the future decision of the Masonic Order to go dormant are sources of misery for my father. In other words, it means that the Order terminated its activities because it was morally impossible to legitimately continue in a new totalitarian regime. What was at first perceived as very difficult, becomes later totally impossible. My father recalled that during the last Ceremony of the Národ Lodge, many Brethren cried after the light was ritually switched off.

In 1951, our Order went dormant but was not entirely dead. Brethren maintain personal contacts, they even sometimes organise improvised Masonic Ceremonies. One of the groups of Freemasons, consisted mainly of members of the Dobrovský Lodge in Pilsen, gathers sometimes together in Mariánské Lázně, where Bro. Mates, director of a local balneotherapy institution, helps to organise the meetings. Bro. Sloboda, Worshipful Master of the Dobrovský Lodge was even presiding over a Conference Meeting. Second place, where Brethren meet after the dissolution of the Order, was situated in Orlické hory. According to my father’s memoirs, several informal Ceremonies were held there, in the forest near a fortification complex called Adamova Hora. It was literally a “Ceremony under the open sky”. Above all, I recall Bohouš Heran, who was a violoncello player and an Organist of the Order. I remember one of the meetings of my father’s friends, mainly elder gentlemen, in black suits and white shirts, who gathered in my grandfather’s villa in Prague. We did not talk at home about Freemasonry, apart from the storytelling, when my father and I were alone at home.

At the beginning of the 1960s, my father gets an invitation to the Ministry of Interior and is given an offer to collaborate with StB (translator’s note: StB or State Security was secret police in communist Czechoslovakia). He refuses it by sending a recorded delivery letter, whose text I had read before it was sent to the StB officers from the Ministry of Interior. After slightly more than a year, my father is arrested (with several other friends – not Masons) and sentenced for subversive activity, owing and writing samizdat, and similar issues. Before they began with protocol interrogation, the first sentence, my father was told was: “You did not think, when you refused our offer to cooperate, that we will get you so soon, did you?”

After the sentence, my father is imprisoned for two years in a prison in the Slovak town of Ilava. He later becomes a prison doctor there. As a consequence of his results in this position, he is released after a year and a half at the request of the prison director. My father shared his prison cell with a Slovak catholic priest, who earlier studied and worked in the Vatican. He told my father about a document that he came across in the Vatican library. The document concerned Jesus’s stay in Alexandria before his return to Palestine. It described Jesus as a distinguished Alexandrian τθεράπευτές. It could mean doctor, healer or an important member of the Alexandrian branch of Essenes, known as “Therapeutae”. Anyway, the priest was more than happy by his discovery and wanted to make it published. His superiors talked him out of doing that, saying “the profane public would understand it in a wrong way”. My father had always respected Jesus as a historical figure.

While being in prison, my father contracted a tuberculosis, which he tries to recover from after his release. The Order has already gone dormant but never completely died. During my father’s imprisonment, our family was receiving financial support from Masons, mainly from Brethren of the Dobrovský Lodge in Pilsen. For me, it still remains the most meaningful evidence of the strenght of the Order’s moral tradition.

One of the last Masonic meetings before the Velvet Revolution took place in the flat of my father and his second wife Mariena in Pankrác in 1968 during “ the Czech spring” movement toward democracy. Eight members participated in this meeting and the question of whether it is appropriate to make the Order legal again was discussed. The decision was to wait as it was not clear if the Russians would invade Czechoslovakia or another unforeseen situation would happen that would stop Czechoslovakia to be free again. The fears became true, the Soviets invaded the country and Czechoslovakia was not free again. Living Brethren, with whom my father kept in touch, did not meet until after the Velvet Revolution.

During the process of “normalisation” as the tightening of totalitarian government on Soviet order was initiated after 1968, my father became a Charter 77 signatory, which was a very dangerous act for a person, who was in prison before for political reasons. He loses his job in Prague and needs to commute for work to Příbram and later to Benešov. His second wife Mariena supports him during the difficult years of “normalisation” and afterwards until the end of his long life.

After the Velvet Revolution, my father is one of the 28 Brethren, who reinstated the light into the Order. With their contact information, he tries to find out, which Brethren are still alive as he plans to gather them together. They meet for the preparation of the Order restoration, sometimes even in his flat. 19 out of 28 living Brethren are of sufficient health to initiate the Masonic ritual of reinstating the Light to Lodges. Not only domestic Brethren but also many international guests (e.g. from the USA or Finland) participated in the ritual of reopening the Order which was dormant for 39 years. Thus, it became an international event. Three pre-war Lodges were re-established: Národ, Most and Dílo, and also one Slovak Lodge. The Order then initiated an effort to swiftly gain new members. During the First Czechoslovak Republic, the Order had about 1000 members, after WWII, there was only a half. 19 Brethren remained for the ritual of reopening after the Velvet Revolution. New Brethren were initiated immediately after from the circles of people, who the living Brethren knew personally.

My father was elected the third Worshipful Master of the Národ Lodge, after Jiří Syllaba (who became the Grand Master) and Václav Rejholec. After two years, he leaves the office of the Worshipful Master, but he takes the position later back for another year because the newly elected Worshipful Master unexpectedly resigns at the very beginning of his first Ceremony in charge. My father calmed the chaos among Brethren and “picked up the Worshipful Master’s gavel”, which means he filled the position of the Worshipful Master for another year. According to Bro. Jan T., he made a brave step in giving the maximum opportunity to newly initiated Brethren. Among the newly initiates, who my father brought to the Order, was also Petr Jirounek, future Worshipful Master of the Národ Lodge and the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of the Czech Republic.

My father was indeed later the Worshipful Master of the Národ Lodge, however, his influence on the Order as a whole was not initially visible. He had crucial discrepancies with several Grand Masters and one Deputy Grand Master about the role of the Order. My father supported the openness of Freemasons towards the public and a merger with other Lodges existing in Bohemia at that time. His propositions and ideas were implemented much later. When Petr Jirounek became the Grand Master, he was inspired in his decentralised reorganisation of the Order by my father’s ideas about the structure of the Order.

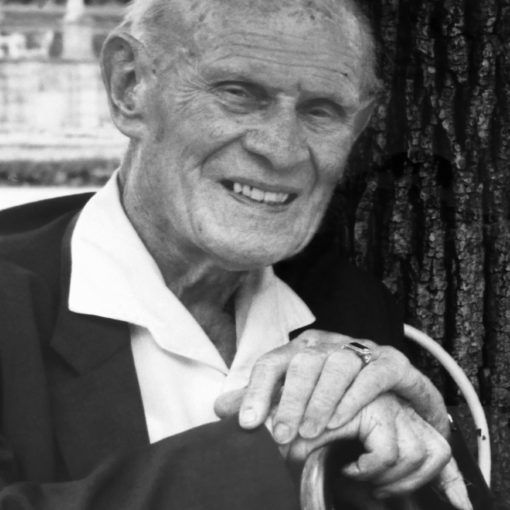

Even though my father could not attend the Ceremonies at the end of his life, he still observed carefully what was happening in the Order. Every Monday, after the Ceremony of the Národ Lodge, he always wanted me to tell him all the news in the Lodge and the Order. He was also happily receiving visits of his fellow Brethren from the Národ Lodge, mainly of Petr J., Petr K. or Martin G. He supported the act of merging the Order with another Masonic Obedience – meaning organisation – which was created after the Velvet Revolution. After all, the merger was proposed by my father during one of the summer John the Baptist Ceremony in the 90s, which was held at the Kozel chateau.

My father lived till his 97 years. He had two features above others: fearlessness and love of truth, which was also connected to his love of science. He wrote 301 scientific articles and 6 scientific books. At the brink of his life, he wrote his first memoirs „Symptomy bezmoci: vzpomínky“1 (The Symptoms of Powerlessness: Memories). The Chapter “Nejtěžší zkouška” (The Hardest Test), describing the times from his imprisonment to the release from the prison in Ilava, was written twice. Once during his visit to my home in Chicago, USA. He did not want the fully true but condemning-the-normalisation text to be found in case of a house search in his Prague flat or another arrest. After the Velvet Revolution, he finished the second version of the text about his most difficult victimisation. Afterwards, he wrote other memoirs, this time more personal and optimistically named “Střípky naděje”2 (The Fragments of Hope). It was published by OMIKRON publisher in 2004.

My father loved classical music. He thought that it is an inherent part of the Freemasonic tradition. He also admired poetry, from which he picked a poem by Otokar Březina called “Stavitelé chrámu” (The Builders of the Temple) as very important for all Freemasons. For his activity in the WW2 resistance, he was awarded after the Velvet Revolution by the association of the Charter 77 (a dissident movement active during “normalisation”).

Written 19. 1. 2012; modifications 3. 3. 2020, 7. 9. 2020, 13. 9. 2020

Michal Wagner, son

1 Wagner, Vladimír: Symptomy bezmoci: vzpomínky. Praha: Galén, 2003. ISBN 80-7262-216-1.

2 Wagner, Vladimír: Střípky naděje. Praha: OMIKRON, 2004. ISBN 80-903563-1-1