Going through the list of Brethren, who were members of the Národ Lodge, we can also see a name of an architect that has resonated in my daily life as a boy from Zlín every day. One of the streets, where I spent my childhood, was named after him. I would not have even thought back then, cycling on “Kotěrka”, that it was named not only after a known Czech architect but also a Freemason Jan Kotěra. I also would not have thought that while visiting my friend’s house that we were in the last preserved Kotěra’s worker’s house with a mansard roof. With its ocher plaster, it stood out of the rows of Zlín’s brick houses.

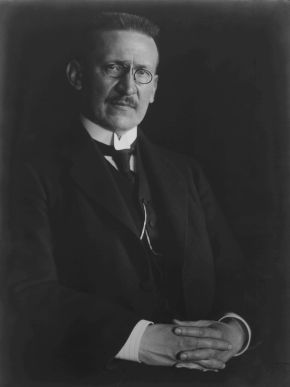

Jan Karel Zenko Kotěra was born in Brno on 18 December 1871 to a Czech-German marriage. He was brought up in German schools initially in Dolní Zálezly and Ústí nad Labem and then at the state industrial school, Vocational School of Construction in Pilsen. He graduated in 1890 and continued to the Prague design office. In there, prof. Freyn discovered his talent and with baron Mladota of Solopysky, they became his patrons and sent him to further studies, this time to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna under the tuition of professor Wagner. Here, he meets Adolf Loos and Jože Plečnik. In 1897 he is awarded a very prestigious Roman award that is linked to a scholarship in Rome. From Rome, Kotěra brought back many sketches and materials that he uses in later years. With this scholarship, his studies end.

After his return to Prague, he teaches at the Prague School of Arts and Crafts, where Josef Gočár is one of his students. Later, Kotěra was named a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, where he taught, among others, František Lydie Gahura.

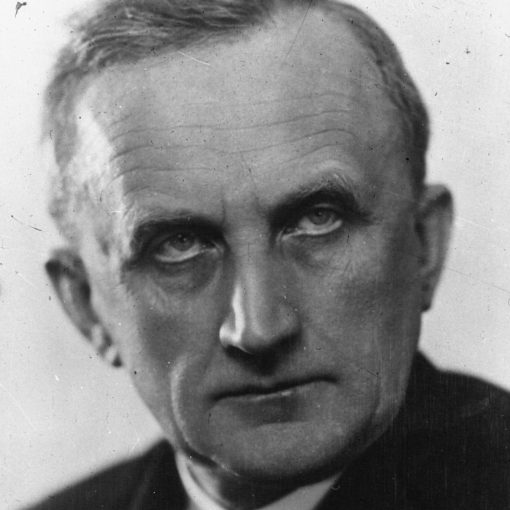

Let’s get back to Moravia for a while, specifically to Zlín that is in those years at the beginning of a new era. Tomáš Baťa laid foundations of a new shoemaking giant (at least for that time). Development and transition of the family company to a factory bring a need to expand the infrastructure and the whole city. Next to the shoemaking factory, there are new engineering companies, a paper mill, and tanneries. People from surrounding villages flow into Zlín with whole families to find a job, which brings a need for new houses. Therefore, Baťa met in 1915 with Kotěra and other architects, who came up with an urban and regulating plan for the workers’ quarter called Letná. His plan introduced the core streets that were encircled by Zlín’s famous single, semi-detached, and quadruplex houses in the 20s and early 30s. About 2000 of these houses were built in Zlín and their lifespan was planned for 20 years. After that, they should have been pulled down and replaced by new and modern ones. Houses that were not destroyed during WWII are still standing, even after more than 100 years. They are continuously reconstructed and rebuilt but still many of the original houses remain here. The final form of the Letná district was created in the 1930s by the aforementioned František Lydie Gahura. Another important building in Zlín, which comes from the workshop of Jan Kotěra, is the Villa of Tomáš Bat’a, which is one of the most important historical buildings in Zlín. Bata had it built in 1910 according to a design by local builder František Novák, but soon stopped the whole project in dissatisfaction and approached Kotěra to rework the original design. That resulted in a house that combines the popular concept of an English family residence and Kotěra’s much-loved neoclassicism. It was the cooperation on this construction that started Kotěra’s further activities in Zlín. His name is thus permanently inscribed in the history of the town. Just like the names Karfík, Gahura, Kubečka, and Le Corbusier, who was not active in design activities, but was a kind of silent observer, advisor, and admirer of Zlín architects.

But to return to Jan Kotěra and not just admire the Wallachian brick buildings. Let’s list some examples of his work here in Prague. One of his modernist buildings is the Villa Bianca in Prague 6. To give you an idea, it is a villa in the now-closed complex of the Russian Embassy residential buildings, where Korunovační Street turns into Pod Kaštany Street.

Another object that can be seen in Prague is Peterka’s House on Wenceslas Square. Since 1900, it has been the seat of the Lidová Banka (People’s Bank) and the banker Peterka lived in one of the flats – the house is named after him. The building is built in the Art Nouveau style and at the time of its construction was the target of harsh criticism by Prague architects.

Probably the most famous building that was built in Prague in Kotěra’s design is the building of the Faculty of Law of Charles University. The project was designed as early as 1907, but the construction itself was started after Kotěra’s death and was led by architect Ladislav Machoň, who fully respected Kotěra’s design. Perhaps we can assume that in the gable of the building we see the Delta, which Kotěra would have used to express his affiliation to our Order.

Of course, I must also mention Kotěra’s own villa on Hradešínská Street, No.6. It combines rough plaster and masonry and is dominated by a kind of entrance tower.

Kotěra’s work is not limited to Prague. In Prostějov, we can find the monumental National House, which merged the social, theatrical and otherwise cultural life of the city. In Hradec Králové, the District House, the Museum and small buildings on the Prague Bridge over the Elbe River were built under his direction.

Another interesting episode is the realisation (if you want to say non-realisation) of the villa of Karel Kramář and his wife Nadězda in Crimea in the town of Barbo. Apparently, one of the reasons was a proximity of Karel Kramář to our Order – Kramář approached Kotěra with a wish to design the villa. Today, we can only draw information from the archives of the National Technical Museum, or from private correspondence between Kramář, Kotěra, and a mutual friend Machar (also M.), so in the words of curator Stehlíková we can read: ‘All scholars to this day mistakenly believe that Kotěra did not complete the villa project in protest against the incompetent interference of Mrs. Kramář and that someone else’s design was implemented.’ However, he does not attempt to reconstruct Jan Kotěra’s contribution to the final project of the Crimean villa, but only states that “if we compare the contemporary photographs of the finished Barbo villa with Kotěra’s projects, we find that the style corresponds to the line of Kotěra’s monumental work.” In the correspondence between Kotěra and Kramář, we can also read Kramář’s plea to please Mrs. Naděžda, to give in and finish the project: ‘It will not be difficult for you to do something for me out of friendship for me. Am I not mistaken?’ Kotěra answered: ‘If you and your mistress do not like my proposal, I will get a Renaissance assistant, I have one here, he is my friend.’ Who he was, we will not know today. The entire correspondence between the Kramář family and Kotěra is written in the article ‘Mými principy, mojí řečí, mým slohem‘ (My principles, my speech, my style) by Ladislav Zikmund Lender.

Kotěra was not only the founder of Czech architectural modernism. In his designs today we can also find references to Gothic and Antiquity. This made him controversial for many of his contemporaries and he was the target of frequent criticism. He was, of course, an urban planner, draughtsman, painter, and war activist in the Mánes association. He died on 17 April 1923 in Prague and is buried in the Vinohrady Cemetery.

Delivered by Bro. Filip Ob. on 4 April 6022